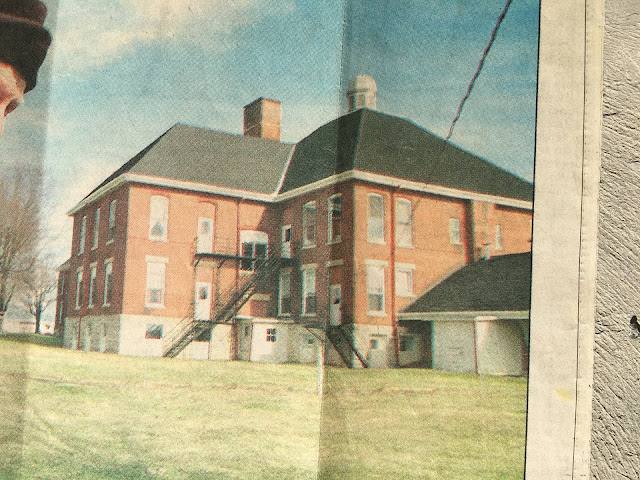

On the first floor of a massive red brick building along U.S. 27 lives John Doty, a quiet, fragile man who, for all practical purpses, barely exists. He is 79 years old and has never driven a car, flown in an airplane, made or received a phone call, held a job, filed income taxes, read a book, written or received a letter or held a woman.

John Doty lives in a tidy 8-by-10 foot room with a window, a cot, a metal chair and a small dresser and bureau. The toilet, sink, shower and TV are down the hall. He owns six pairs of underwear, seven shirts, two pairs of pants and two pairs of shoes.

A lifetime of possessions rests atop the bureau: a birdhouse, a tiny Santa Claus, a stuffed rabbit, a toy ship, a round mirror and a blue plastic comb with which he parts his thin white hair. The walls are bare. No photographs.

"I've lived in this room since I was 21," John Doty says in a barely audible mumble. He stares at the floor and wrings his hands.

"I never figured out where I was born."

He has a severe speech impediment, which in 1939 was enough excuse for his half brothers to declare him stupid and useless and to place him here in the Randolph County Infirmary.

"I got used to it, he mumbles, "I used to feed the chickens but they died. Now I watch Guiding Light and As the World Turns."

John Doty has no living relatives or any friends beyond the four men and seven women who live with him in the imposing red brick building.

Whatever John Doty is, was or could have been is now lost. Whatever dreams or asperations he once had have long since vaporized and vanished in the mist of the long, dull years he's known. He's not a prisoner. He could leave. But where would he go? What would he do? He can neither read nor write. The damage has been done.

After 58 years of institutionalization and regimentation, he can't make eye contact with new people. He eats alone, he watches his two soap operas alone.

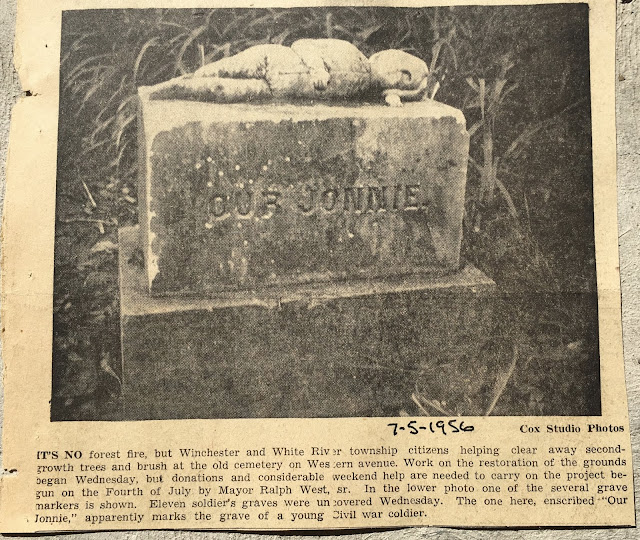

The Randolph County Infirmary is also known as the county old folks' home, or the poor farm, as people called it when it was built in 1898.

Luckily for John Doty and the 11 other people who live here, David and Susie Burge began running the home for the Randolph County Commissioners in July 1994. They even gave it a new name; Countryside Care Center. Its exterior may not be inviting, but the three-story, 68-bed, 29-room facility is cheery and spotless.

David promised John Doty he will buy him some laying hens in the spring.

"We can buy eggs cheaper but John likes feeding chickens so I told him I'd get some new ones," said David Burge, 52, who accepted the $20,600-a-year, seven-day-a-week, 24-hour-a-day position when he lost his longtime job as a toolmaker in some corporate shake-out.

David and Susie live in the building. Susie cooks three meals a day for the 12 people and does all the laundry and housekeeping. She is paid $15,500 a year. The 99 year old building sets on 350 rolling eastern Indiana acres. Maintenance on the fortress-like building, with its 18-inch thick walls and 12-foot ceilings, is non-stop. It took David a year to paint the floors. He does all the repairs and struggles through extensive county, state and federal paperwork to house 12 very delicate people with some degree of dignity.

He also drives them to the doctor and takes them shopping for cookies and candy. He organizes holiday parties, brings in groups to entertain, religious people to preach and more importantly, treats them like human beings.

We don't run this place as an institution or a nursing home. This is a home," said David, who has no formal training in caring for old people.

He operates on a $120,000 annual budget from the county and has made the place self-sufficient. One or two more residents and they'd make a profit. He leases out the farm and pasture land to local farmers.

Those who can afford it pay $811.20 a month for room and board. Those who can't and are eligible are covered by state money and Medicaid.

"If you're under 65 and not disabled. you pay your own way," he said. The two men under 65 are disabled and covered by Social Security. One is a stroke patient, the other a brain-damaged alcoholic who has the entire third floor to himself because he won't bathe. He's been up there seven years.

At one time all 92 counties operated homes for the poor. Only 31 remain, housing about 500 people. Many of the old places were dungeons, a dumping ground for the emotionally disturbed or men like John Doty, whose parents died and whose half brothers abandoned him.

Two years ago, the Randolph County Commissioners thought about closing the place to save a few dollars, which might have been disastrous for John Doty and several other residents who've known no other home.

Commission President David Lenkensdofer of Union City huddled with David Burge and figured out a plan to make the place self-sufficient. They painted the interior, installed bright lighting and held several open houses so the public could see what a fine facility it is.

In an effort to recruit new patient, they even worked up a brochure pointing out the home charges one-third less than a comparable nursing home.

The Commission relented.

"I was going to fight closing it to the end. We're close to breaking even and David and Susie are doing an excellent job and really care about those people," Lenkensdofer said. "as long as I'm commissioner, it will be there. We need to show the people of Randolph County we care about people."

And they do.

When the Burges took over, John Doty wouldn't speak to Susie. Women frightened him.

Paula, who is 52, had never worn a dress in her life. Susie bought her one. Paula no longer jams her finger her nose and hemorrhages from a nosebleed when she gets nervous. She even smiles when she plays with her Barbie doll named Jennifer.

"I guess we're stupid." says David, "but we take a real interest in this place and these people. We have a soft spot in our heart for people nobody gives a s___ about."

Doris M. Addington, who is 82, has been institutionalized since she was 11, the last 52 years in Randolph County. Her father Cressin Addington, was put into the home eventually too, nobody is sure exactly why. He died here.

Like John Doty and other people who were admitted a half century ago, their entire official file consists of one single, yellow piece of paper.

Robert O. Tharp's file says he was admitted because he was "retarded, can do farm work with supervision" That was 32 years ago. He's an old man now.

Most files simply list the resident's date of birth, birthplace and parents names. No reason why they were admitted, nor what, if anything, was wrong with them. Essentially, someone dumped them, at a time when a child had no more rights than an abandoned dog.

On the second floor behind a locked door is a reminder of the past; a black, steel jail cell, a cage eight feet square with a metal cot and a toilet with no seat.

Doris remembers those terrible days.

She had six brothers and sisters when her mother, Nettie Clevenger Addington, died. Her father had a problem of some sort, nobody is sure exactly what, and a state official came in and scooped up the children.

"A lady said she'd take us uptown but she took me here. She was a mean one. She took the others to Grandma's house and they was all adopted out but they told me I was too old and nobody wanted me."

"When they took my baby sister, I fought those people. They lied to us kids. I fought like a tiger," explained Doris, leaping around and swinging her fists to demonstrate how she fought for her baby sister.

Doris had a nervous breakdown and went blind. She spent 10 years in homes in Fort Wayne and Indianapolis and was returned here when she was 21, just in time to see her father die of a heart attack in the dining room.

Her eyesight has returned, somehow.

"With God's help I got this far." says Doris, a delightful, charming lady.

"In the old days it was like a dungeon here. Terrible things were done."

Like what?

She turned away and cried, then later mentioned something about some boys taking her someplace in a car.

Colleen Duvall, 68, cries once a year, on Mother's Day, because she never hears from her only son. She writes him every week.

When the Burges took over, they were startled at the regimentation in the home. Later they were struck by how difficult it was to change that.

A deafening air raid siren blasts everyone out of bed at 6:30 a.m. Men live on one side of the building, women on the other. Before meals, they assemble on benches outside the dining room. A partition separates the male and female waiting areas.

At 7:00 another air raid siren screams through the building and they shuffle into the dining room to eat. A partition separates the dining room. The air raid siren summons them to lunch and supper and the 8:00 p.m. snack time when everyone gets a cookie or cupcake before bed.

The Burges figured the air raid siren was a little much. It was like calling cattle. Besides, the residents can all tell time and remembering 7 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 4:30 p.m. and 8 p.m. cupcake hour isn't difficult, especially when your entire world orbits around meals.

They also proposed integrating the dining room and the activity room, men and women mingling.

Paula stuck her finger in her nose and had to wear mittens for a week. She wouldn't play with Jennifer. John Doty quit talking and boycotted Guiding Light. The alcoholic threatened to bathe, Colleen began crying. Doris, who chatters all the time, grew sullen. It was a mess for a couple of days, until Susie assured them the air raid siren would continue to blast and men and women didn't have to eat or watch TV together.

"If you change the least little thing they come unglued," said Susie of her attempt to nudge life into the 20th century before the 21st century begins. A major crisis was averted.

In an effort to eliminate the stigma of a county home, the commissioners at David's urging recently changed the name and he has actively begun recruiting new residents.

One newcomer is Virginia Monks, 95, widow of Sen Merrett Monks. He died 31 years ago and she ran a home for women for 45 years until she got too old. She moved in six months ago and lives in a pleasant converted ward.

"It's not home, but I recommend it to anyone," Virginia Monks says, clutching her Bible in preparation for a visit from Margaret Bunsold and the ladies of the Main Street Christian Church.

The four church ladies file into Virginia's room, followed by Doris, Colleen, Julia, Paula and her Barbie doll, Jennifer.

Margaret Bunsold commands everyone to please be seated and be quiet. Today's lesson will feature Matthew 19:26 and the importance of obedience, she announces.

Cheerful Doris wants to talk about something more fun, since after 62 years in institutions she's well-drilled in obedience skills and taking orders.

"We need to learn obedience," Margaret Bunsold scolds Doris. "Have a seat, Doris. God wants us to obey. We're here to learn obedience, the Bible teaches obedience."

Doris obediently sinks in her chair. Margaret Bunsold proudly notes that her daughter, "my Tasha," will embark on a soul-saving mission to Mozambique this summer. Everyone should pray for "my Tasha." Mozambique is a poverty stricken, war torn place sadly in need of Tasha's spiritual help, she says.

"God says there will be no peace on earth until He comes back, she lectures.

"But there is peace," Colleen interrupts.

"Not really, honey. Please be still."

Colleen sinks in her chair.

Obedient.

Down the long hall across the building, John Doty has retired to his room awaiting the screeching suppertime air raid siren. He sits on his metal chair staring out the window.

Both hands are folded on his lap. Guiding Light and As the World Turns are over. Two hours until supper.

Last summer, when the old chickens stopped laying eggs, John Doty was confused. Why? he wondered. For 57 years he'd been collecting eggs at 3 p.m. David took the chickens away and told John they'd gone to the old hen rest home.

John quit talking for several months. His sole purpose in life and reason to exist had been eliminated.

David quickly surveyed John's devastation and promised 10 young laying hens in the spring.

After several long, silent moments, it's obvious John Doty is staring at the chicken coop and that he does this every afternoon for two hours.

"I'm waiting for my chickens to return," he mumbles.

Count your blessings.

The Indianapolis Star, March 31, 1997 by Bill Shaw.

.jpeg)